thinking about loneliness [on television]

How does television capture something so intangible?

What is loneliness? “Sadness because one has no friends or company,” and “(of a place) the quality of being unfrequented and remote; isolation” both seem like unjust definitions, too-literal ways to define an experience that feels knottier, more complex. I can tell when I feel lonely because something is missing — connection, empathy, a sense of understanding, a warm body near mine, or sometimes, just crushed by the weight of existence. On other days, I can be alone and feel connected just the same. While watching the new season of Only Murders in the Building, I’ve been thinking about how such a transient experience is translated to television through characters and world-building, and also the relationship between television and loneliness that exists outside of the text itself.

If you Google “loneliness television,” you will mostly find empirical studies seeking to try and understand how television contributes to or alleviates feeling of loneliness. Some of them link television viewing habits with lifestyle and physical activity, some of them seek to make psychiatric diagnoses from afar. There is a long history of this, of course.

Television studies wasn’t founded for textual analysis of television episodes in the way of art history of film studies—there was no way to access episodes pre-VCR outside of watching a live broadcast on the big (only) three networks (a movie, you could go see as many times as you’d like). There’s also the feminist television studies perspective: that television wasn’t taken seriously because it was feminized as an object of study, seen as mass culture as well as its physical presence in the home, the realm of the “domestic.” So anyway—needless to say, when I was poking around for academic work on loneliness, there was barely anything, except for a book chapter I’ll get to a bit later.

I’m constantly itching to write about loneliness. There’s so much I want to say about it, but I’m never sure how much of myself to leave on the page. There were certainly periods of my earlier 20s that felt lonely, but as I face my 30s, I’m realizing there’s a layer of loneliness I hadn’t even considered when you’re trying to gasp for air outside of a 9 to 5, disconnected from avenues of new friendships without more free time or a school setting, unconsciously comparing yourself to everyone on social media, not to mention waking up to realize all of your friends are getting married seemingly simultaneously while you cuddle with your cat and new episodes of Starstruck at night instead.

Television writers (who are now able to write TV again, YAY) have a profoundly challenging job capturing loneliness and how it manifests. Between stakes and relationships and arcs, there’s little time to depict the quiet and endless hours of loneliness, or to accurately represent what is a very internal, conflicting swirl of emotion. And yet, we hear about loneliness all the time: about how it’s an epidemic shaving years off of our lives, how we fared during pandemic restrictions, how technology is pulling us apart rather than closer together, how church communities have been replaced by worshipping at the altar of celebrity. On the macro scale, loneliness in our culture is evident, but on the micro, it still feels taboo or counter-culture to talk about.

In Atlas of the Heart, researcher-storyteller Brené Brown writes: “We experience loneliness when we feel disconnected. Maybe we’ve been pushed to the outside of a group that we value, or maybe we’re lacking a sense of true belonging.” According to her (and disability justice activists), our genetic and neural makeup is predisposed to interdependence rather than independence. We are hard-wired for connection, and yet so much of the Western world is constructed in ways that fuel disconnection. You’d think this is something we would’ve figured out rather than make worse in modernity.

I think the loneliest I’ve ever been were the years in graduate school when my days would consist of going to the library and coming back to my studio apartment without uttering much of a word (except “I’ll have an oat milk latte,” mid-day). There were a few months of this, sometimes weeks on end, where what I had hoped would be academic solitude shifted to something more nefarious, where emotions like shame, sadness, and depression left its familiar grey tint over every day life. I slept fourteen hours a night, smoked a lot of weed, and isolated myself from friends, thinking if I could just rest a bit longer I would have enough energy to build friendship or date, forgetting connection’s energizing, regulating effect. It became a self-feeding loop.

But I’ve also experienced loneliness on a spectrum of experiences: after a romantic rejection, in high school trying to navigate my sexuality in a homophobic culture, in the mid of Pacific Northwest winters when the rain just won’t stop and it’s easier staying home than getting drenched on your way to meeting someone at a bar. There were also flashes of loneliness this past summer, when I was trying to make full-time writing work in a financially feasible way during the strikes, and could barely leave my apartment due to a poorly-timed broken toe. For a moment there, I felt transported back to those graduate school years—this time, with more self-awareness about how important it is to be connected to other people. I realized I don’t do well in precarity. Then again, how does anyone?

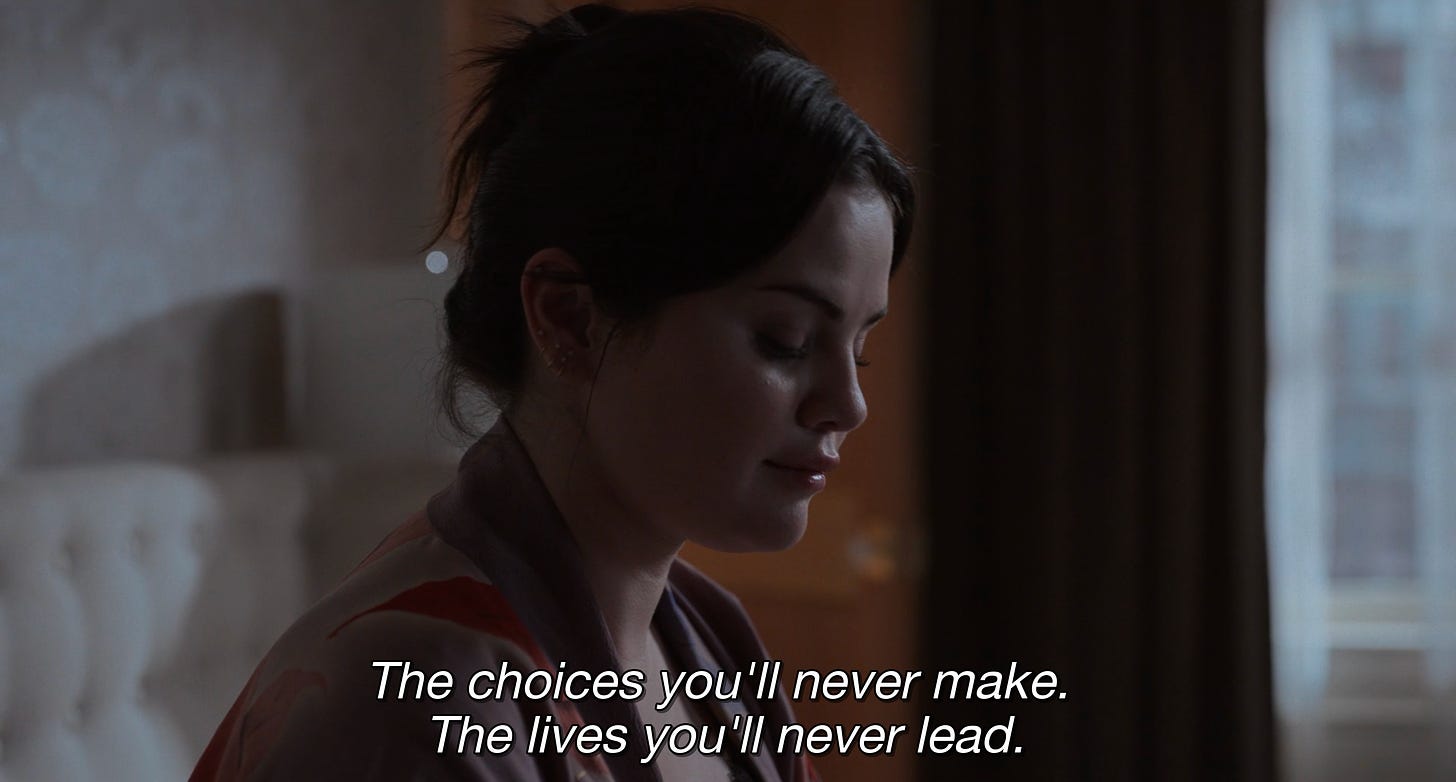

The problem with the aesthetics of loneliness on television is the challenge in depicting that experience without it being an absolute bore to watch. Sure, there are a ton of fleeting, character-specific moments of loneliness on television, like Rachel Fleishman (Claire Danes) feeling maddeningly alone in her experience of postpartum depression on Fleishman is in Trouble, as one example. This new season of Only Murder in the Building, which sparked my thinking for this newsletter, does a poignant job depicting loneliness for struggling creatives in New York. Meryl Streep plays an aspiring actor who has spent her entire life trying and failing to break into the industry, and many of the other characters reflect on what could have been in their lives and careers—and how life, eventually, beats them down until they stop aspiring to their dreams. Oh, and I guess there are also the lonely men of prestige TV. Don Draper was lonely as hell.

Other shows, particularly sitcoms like Friends or How I Met Your Mother, “feed their cheerful narrative stock primarily from the countless (and only at the end successful) efforts of their characters to establish successful (couple) relationships as a way out of their tortures of loneliness,” writes academic Denis Newiak in his book chapter, “How Television Produces Invisible Communities in an Age of Loneliness: A Detailed Look at 13 Reasons Why.” Romantic couplehood is often constructed as the silver bullet to loneliness, on television and otherwise (we all know it isn’t…right?).

I believe loneliness has to be woven into the world-building of a show rather than through a literal depiction of a lonely character in order for it to feel more representative of the experience. Space (The Expanse, Battlestar Galactica) and the apocalypse (Station 11, The Leftovers, The Walking Dead) are vast playgrounds for loneliness in that regard. Who wouldn’t be lonely on a spaceship away from home, floating in nothingness?

Loneliness in modernity is much more challenging to depict, though. As Newiak astutely writes: “In numerous successful television series of the recent past, discourses of loneliness dominate against the societal background of increasing individualization, urbanization, and medialization, as they decisively shape the late-modern way of life.”

Mr. Robot is the perfect manifestation of loneliness as broader than the solitary experience of aloneness. Loneliness for Elliot (Rami Malek) is made literal in his inner monologue made privy to the viewer from the first episode, his rants about capitalism, structural inequity, the super-rich and how he feels alone in his acute awareness of how these systems are crushing us down.

For all of his vigilante brilliance, ability to hack major companies and self-awareness (well…self-aware to a certain extent, without spoiling the major twist of the first season), Elliot constantly muses at how singularly alone he feels, and he frequently turns to drugs, or a deep psychological denial, to suppress how lonely it feels to be awakened to the dark truths of the world. His loneliness, then, isn’t necessarily his depression or lack of romantic connection, but the gap between his understanding of the world and the reality, and his powerlessness to stop the consolidation of wealth and power despite the best of his abilities. That’s a lot for one person to carry.

Less high concept, but I was initially surprised by how Fleabag reached such a wide audience for a relatively niche, auteur project. It may have been, hot priest aside, Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s uncanny ability to capture loneliness through inner-monologue and self talk as a coping mechanism against grief and the woes of every day life. I also think about High Maintenance, an underrated gem of an anthology series that follows various clients of a weed dealer in New York City, with many of its vignettes about characters seeking connection—perhaps with others (via weed), and sometimes to themselves (via weed).

I actually think watching shows like Fleabag, High Maintenance, Mr. Robot, and even Only Murders in the Building, makes me feel less lonely. A balm, like having a deep conversation with a good friend. Something, something, representation matters. I could never tell you how I would write loneliness for TV, but when I see it represented, it hits a very deep, human, empathetic note as a viewer, since I know that experience so intimately. Television, generally, is also a satisfying temporary placeholder for human connection. I get to dip in and out of endless worlds and character relationships, some close to my reality and others in galaxies far, far away.

According to Newiak, television series “contribute to the creation of strong experiences of community, which late-modern people depend on in order to survive the loneliness that dominates their lives,” he writes. “It is easier to live a modern life with television than without it.”

I recommend The Lonely City by Olivia Laing - a fantastic book: “There are so many things that art can't do. It can't bring the dead back to life, it can't mend arguments between friends, or cure AIDS, or halt the pace of climate change. All the same, it does have some extraordinary functions, some odd negotiating ability between people, including people who never meet and yet who infiltrate and enrich each other's lives. It does have a capacity to create intimacy; it does have a way of healing wounds, and better yet of making it apparent that not all wounds need healing and not all scars are ugly. “

thanks for sharing your lonely times with us. xx