The TV Scholar interview series brings real-life television scholars to my newsletter to discuss their journey to television studies, share nuggets of wisdom from their research, and obviously, to talk about television itself.

This time I chat with Helen Wheatley, Professor of Film and Television Studies and co-founder of the Centre for Television Histories at the University of Warwick, about death on television in all of its forms based on the research for her latest book, Television/Death, published earlier this year.

Before we get into it: what are you watching and enjoying lately?

Oh my goodness, I've so got no time for television at the moment. I've been going back over some old stuff with my kids. My kids are all teenagers, so they're starting to get interested in telly that I like too. We've been watching Sex Education. Last year I re-watched all of Twin Peaks with one of my kids. I’ve been enjoying that pleasure of sharing great television together and returning to stuff.

When did you realize that researching television could become a legitimate thing that you could do in this life?

My first degree was in American and English literature, I did some little bits of Film Studies during that degree, including a year in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and did quite a lot of film courses when I was on my year abroad. I came back as a fourth year undergraduate going, I want to do some more film scholarship and I want to take this further. So I applied to do an MA here at the University of Warwick.

I was being taught by really brilliant television scholars like Charlotte Brunson and Jason Jacobs, people that suddenly brought television studies into my life. Of course, I had always loved and been interested in TV. I was working at a film festival and got a call—which would never happen now—saying we've got the opportunity for you to do a PhD and come teach with us. So I came back into the after my MA department as a full-time teacher and did my PhD alongside it in a bit of an unplanned way. It changed the course of my professional life. I'm still here, so it must have been a good move.

What are your foundational TV shows?

Going back to early childhood, they're things that my colleague Rachel Mosley has written about in her book Hand-Made Television. I was really entranced by stop-motion animation for children in the 1970s. There was some really great stuff produced in the UK like Bagpuss and The Clangers, and there was a whole bunch of programs that were steeped in folk traditions from the UK, a bit of melancholy, all of the stuff that I wouldn't have been able to name as a child, but I knew that I loved.

I’ve always been really interested in the gothic and uncanny television. I wrote a bit a long time ago about the idea of the half-remembered text. Something that stays with you not in its entirety, but perhaps moments, sounds, fragments, theme tunes that continue to haunt you as an adult that you were exposed to in childhood. I've never seen it again, I've never seen anybody write about it, but there was a show called Maelstrom which had these dolls that came to life in it, and I'd love to see that again. That was a really early program that was important for me.

Let’s talk about death! How did you come into researching death on television?

I just released the book Television/Death, which is an exploration of death and dying on TV, of grief and bereavement, and of how television archives enable us to access posthumous images. The interest in writing that work came right at the end of writing my previous book, Spectacular Television, exploring televisual pleasure. In that book, the chapter that was about the spectacle of the human body on TV has a significant section, looking at the presentation of the corpse on television. I was really interested in the work of people like Gunther von Hagens, the showman anatomist who made a series of documentaries for Channel Four of live autopsies and showing his procedures. He shows his plastinated corpses all around the world.

I had written about the spectacle of the dead body on television, but also about the limits of spectacle and how lots of programs that are about the human body, in their handling of death, turn back to what we might see as the lived experience of death. So moving away from the science of death to trying to understand how television programs, television documentary in particular, help us understand the experience or potential experience of death and dying, both as a dying person and also as a bereaved other. The writing of that book had ended there, and I realized there was a whole lot more to say and explore about the representation of death and dying on TV.

In the introduction to Television/Death, you ask: “What role do we expect television to play in our understanding of death and dying experiences?” How did working on this book help you understand your own mortality or experience with death?

It really did. I read really widely for this book, quite far beyond television scholarship in death studies work, cultural and social histories of death and dying, as well as work about the emotional experience of death and dying, grief and bereavement. So lots of thinking about the question of why it's important for us to anticipate death. For many people that might sound quite morbid, the idea that we should live with the constant thought that death is just around the corner.

The first part of the book looks at documentaries about death and dying experiences, the middle section of the book looks at everything from ghost dramas that handle the experience of grief and death-related trauma, comedies, and long ongoing dramatic sagas that explore the experience of being grieved, plus the television programming that looks at what might happen after death, like The Good Place.

Looking at all of those programs in a kind of collection made me think about the fact that we ought to live life with the facts of death in our mind. It's not something I write about in the book, but I became interested in stoic philosophy when I was writing it. Epictetus says when you say goodbye to your kids at the end of the day you should kiss them goodnight and think in your mind, you might die tonight. Which is a big challenge, for parents or whoever. But it's an invitation to enjoy life, and to enjoy the moment and to embrace what's happening in your life right now. Collectively, the reading and viewing that I did around the book has shifted my relationship with living as well as dying. And the idea that we should enjoy the moment.

I love that so much. There’s so much to wrap our heads around with death. There’s way more cultural prescription for what to do when you experience an individual death, but so much less on how to process mass death, like what’s going on around the world right now.

I was watching and writing about The Leftovers during the pandemic. It was a real moment for me watching this drama that's all about this society that's been hit by a mass disappearance. Watching that in the context of COVID, in the context of mass grief and bereavement, it was very resonant. And even going back to shows like Six Feet Under as well, I think during that period it was this moment of thinking about how television helps us make sense of the world and make sense of life and death.

There are cultural moments where our minds, our eyes, our thinking, is drawn towards the facts of death. During COVID that was that was one of those times, where we were all atomized in our living rooms at home and alone, but dealing with the massive collective trauma of people dying. So maybe writing the book sort of helped me through that time in a weird way as well.

What was your greatest finding as you researched and worked on Television/Death?

There’s a research story that bookends this book that was important to me and making sense of what the book is about. In the first chapter, I write about a documentary called Remember All the Good Times, which was made with a young artist who was dying of lung cancer and his family. They made this documentary for the BBC in the North West of England that was about their experience moving towards Tony's death and what that was going to be like. I was fascinated by the question of why you would choose to make such a documentary at that really intimate moment in their life. They made that documentary and then Vivian, Tony’s wife, made a follow-up documentary two years afterwards that was about being a young widow.

I became really interested in their story and why they chose to do it. I managed to track Vivian down and she agreed to sit down and talk to me. I was really interested to find out what role it played in their lives going forward. She told me that they decided to make the documentary, partly to give them something creative to do at this really difficult moment in their lives. But also because it was a campaigning move—they wanted to open up national conversation about death and dying. It was at a time in the UK when people weren't told if they had to face a terminal diagnosis. They were saying: face this thing, stare it right in the face.

I felt that learning about that documentary, learning about why they decided to do it and what they wanted to get out of making the documentary and then the difficult history of how they then watched it and how it existed on the edge of their lives was really interesting to me, and told me a lot about the power of television.

That’s such a fascinating research approach, going beyond what you might expect from television studies in terms of methods used.

I’ve always been a bit of a kind of methodological Magpie. Textual analysis is really at the centre of my writing, but it's joined by interviews. I'm always keen to talk to people about why and how television matters to them. The final chapter of the book looks at the city of Coventry, where I live and work and a project that I did to bring archival holdings of programs made in and about the city out of the archive and re-screen them around the city in various ways, and have conversations about why the archive is meaningful, from a kind of personal and civic point of view. So yeah, I also write about other people's reflections on television as well as my own. It’s important to me to build a whole picture of television as an object, whether from the point of view of the viewer, the text, or its production.

Can you talk a bit about the “pornography of death” in US television?

The phrase comes from some work in the 1950s that was about the anxiety about putting death on screen, particularly in relation to US television. There's been an anxiety since the 1950s in the idea that television will expose the unwitting, particularly the young, to sites of death and spectacles of the dead body and sights of murder. Television crime as a fictional and factual genre has brought lots of death into our homes via TV.

On the other hand, particularly in the advent of HD technologies, with the move towards streaming services and more niche content, we've moved towards an era of the greater spectacle of death and dying. Whether it's the flayed body in a crime drama, thinking about things like the presentation of the corpse in shows like Dexter or True Detective. Hannibal is a great example where the art direction team must have had so much fun. Every week’s episode presented a corpse in a more spectacular, more abject, more grotesque way. I'd say the pornography of death has probably stepped up recently. But there has always been that that worry that television programs have somehow reveled in the spectacle of death and dying and that there are viewers, particularly vulnerable viewers, who might be enthralled by that spectacle or appalled by it in different ways.

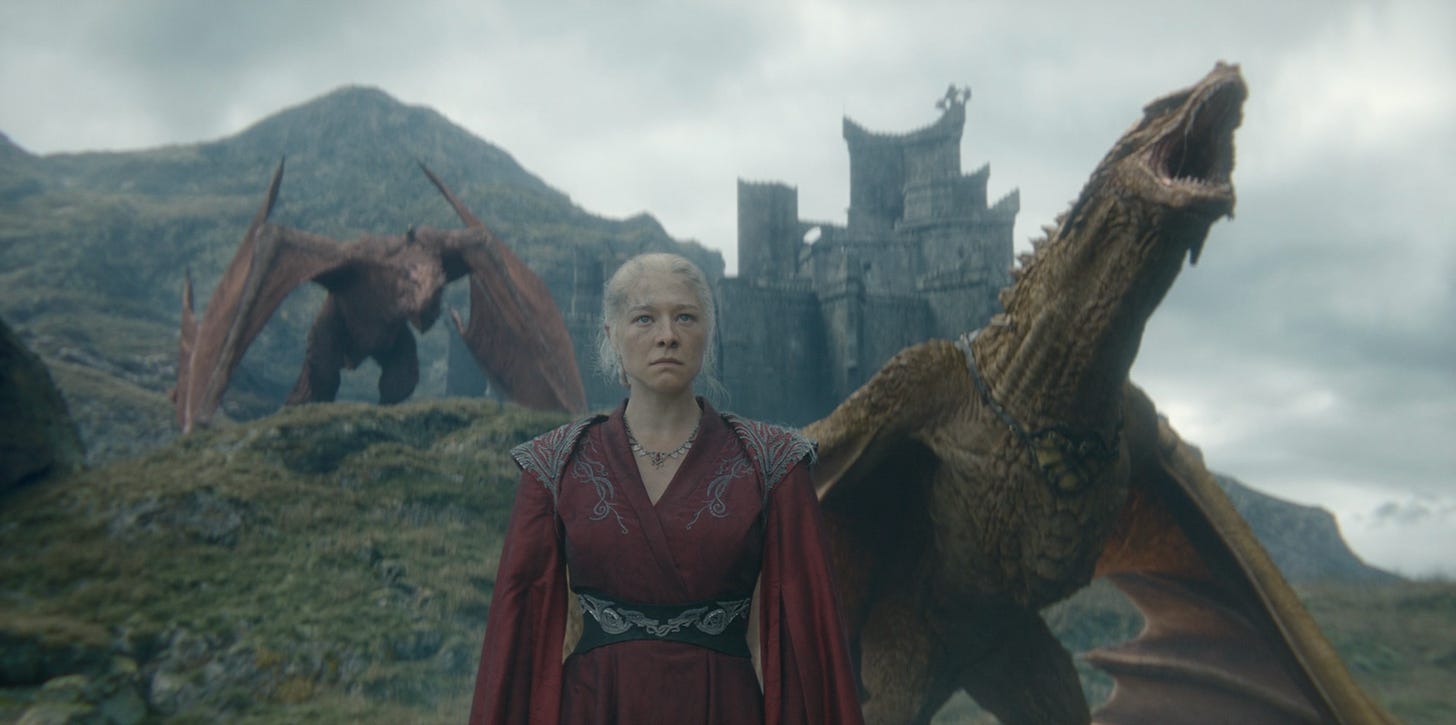

I also draw on the example of Game of Thrones and the Ned Stark Effect. There are a number of brilliant US journalists who write about what happens in sweeps week following the Ned Stark death where all of a sudden we've got these big unexpected, either spectacular or long-standing characters who were killed off as a way to create some buzz and create some drama and therefore bring viewers to the program during sweeps week. Gratuitous and sensational presentations of death as a way to bring people towards television at key moments of measuring audiences is a big thing in the States.

What’s a show you recently abandoned and why?

I started watching the new series of House of the Dragon. I've watched the previous series with my close friend. She came round and I was like, let's watch the first episode of the new series and we can pick this back up. When I watched Game of Thrones, I was really familiar with the narrative since I'd read the books in advance of watching the program. But I don't seem to be able to keep up with House of the Dragon.

I don't know if it's because I'm getting old or I'm tired, but we sat there during the first episode going: What are they doing? Why are they cross? What’s going on? I could not match up what happens at the end of the first season with what was going on at the beginning of the second. At the moment I'm not desperate to carry on with it, because I just couldn't work out what the hell was going on. I don't know if that says anything about the program and it's making or whether it's actually just the extent to which I'm permanently exhausted and unable therefore to keep a narrative steady in my head at the moment.

Thank you for this interview. This idea of half-remembered things is fascinating to explore as a storytelling device.